Summary: This year, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) announced the start of the rainy season on Wednesday, May 29, 2024. This season has several risks to businesses and likely disruptions. Potential damage to equipment and inventory, logistical disruptions, and workforce absenteeism, along with lost productivity to infectious disease and Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD), are routine impacts of the rainy season.

Many business owners in the Philippines admit they fail to project the impact the rainy season has on their bottom line. Some executives find out too late that effective risk mitigation during the rainy season has less to do with preparing for the next super typhoon and more to do with maintaining continuity for the 100 or so days of inclement weather, particularly the flooding. In the words of one foreign executive: “The best way to plan for [the] rainy season in the Philippines is to always be prepared for the worst.”

The Scale of the Rains

Each year the arrival of the southwest monsoon signals the start of the rainy season in the Philippines, which typically lasts from June until November. In addition to the monsoon wind and rains, the country experiences an average of about 20 tropical cyclones each year. A handful intensifies into typhoons and makes landfall. These interact with the southwest monsoon, which may enhance the strength or change the direction of the storm, consequently bringing heavy rains and strong winds for longer periods. So far, the Philippines has had one tropical cyclone – Tropical Aghon in May. PAGASA’s estimate is that 13 to 18 tropical cyclones will enter the Philippine Area of Responsibility from June to November.

The eastern coastal provinces of the central and northern Philippines often bear the brunt of typhoons. Provinces such as Northern and Eastern Samar, Catanduanes, Albay, Camarines Norte and Sur, Quezon, Aurora, Isabela, and Cagayan are usually the first hit by the storms. While there is an absence of consensus, studies indicate that Asian typhoons have grown 50 percent stronger over the last forty years and will increase with climate change. Moreover, the 2023 IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report asserted a stronger link between human activity and extreme weather events like heatwaves, heavy precipitation, droughts, and tropical cyclones. While casualties from these have decreased, economic losses have risen.

Metro Manila’s vulnerability to flooding is enhanced by a number of natural and man-made features. Most of Metro Manila is built on an alluvial floodplain, an area that acts as a catchment and drainage system for water to make its way from surrounding mountains and rivers to the sea. The Marikina and Pasig Rivers, which run beside and through the city, act as the main delivery systems for the water from the highlands that is finding its way to the ocean.

This natural vulnerability is enhanced by urban planning issues. With land in Metro Manila scarce and expensive, the poor are forced to build in flood-prone and high-risk areas. The Metro Manila Development Authority estimates more than 500,000 families live in slum areas in Metro Manila, although that figure is now significantly dated and likely much higher. Metro Manila produces 8,600 tons of garbage per day, about a quarter of which is estimated to go uncollected, and this garbage contributes to the clogging of storm drains and the spread of waterborne diseases. The two dams that service Metro Manila, Angat Dam and La Mesa Dam, must be monitored for potential overflow. Several dams around the Philippines have had to release water because of typhoons in 2020, resulting in mandatory evacuations.

Seasonal Diseases

In densely populated areas like Metro Manila, health risks associated with heavy rains and flooding are amplified due to a lack of sewage and drainage systems and minimal sanitation services. Seasonal diseases can range from mild to severe, pose a serious risk to public health and potentially disrupt business continuity.

Officials at the Philippine Department of Health (DOH) use the acronym “WILD” when talking about some of the more common rainy season illnesses. The term stands for Water-borne diseases, Influenza, Leptospirosis, and Dengue.

Data Disclaimer: As of May 31, 2024, the DOH has not yet released to the public the complete data on the number of cases and deaths for WILD diseases for 2024. Currently, what had been released are piece-meal regional figures. The information presented below regarding WILD cases and deaths is sourced from the 2023 official documents.

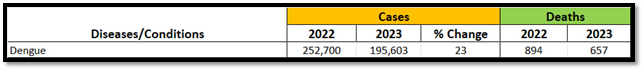

Dengue – sometimes called dengue fever, is spread by the Aedes species of mosquito, which breeds in standing water. In rare cases, dengue can be fatal, so symptoms should be monitored. Sufferers with severe symptoms should consult a doctor. In 2023, the DOH reported 195,603 cases from January 1 to December 2, 2023. This represents a 23 percent decrease compared to the 252,700 cases in 2022. There were also 657 deaths attributed to dengue in 2023.

Many of the rainy season diseases are associated with poverty and poor living conditions. However, Dengue is a disease that also impacts the upper classes.

Waterborne Illnesses – Cholera and typhoid fever are common water-borne diseases in the Philippines. Both diseases are bacterial infections typically contracted from ingesting food or water contaminated with human waste, though typhoid also spreads easily from person to person through close contact. Water-borne illnesses spike in the rainy season but tend to affect communities where more people live in close quarters, although aid workers are also at risk.

Cholera

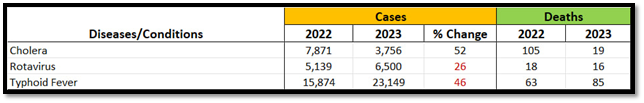

3,756 cases and 19 deaths were recorded in the country from January 1 to December 2, 2023. This represents a 52 percent decrease in cases compared to the 7,871 cases recorded in the same period in 2022.

Rotavirus

6,500 cases and 16 deaths were recorded in the country from January 1 to December 2, 2023. This represents a 26 percent increase in cases compared to the 5,139 cases recorded in the same period in 2022.

Typhoid Fever

23,149 cases and 85 deaths were recorded in the country from January 1 to December 2, 2023. This represents a 46 percent increase in cases compared to the 15,874 cases logged in the same period in 2022.

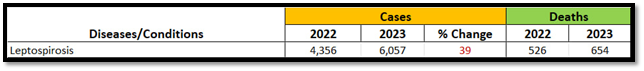

Leptospirosis – Leptospirosis is a bacterial infection transmitted through animal waste, particularly rats, from sewers and trash heaps when floodwaters overflow. The bacteria can enter human food and water supplies through contamination of soil, water and vegetation. The disease however is relatively rare, with an average of 680 reported cases in the Philippines annually, but higher figures in recent years. In 2023, the DOH reported 6,057 cases from January 1 to December 2, 2023. This represents a 39 percent increase compared to the 4,356 cases during the same period in 2022. There were also 654 deaths attributed to leptospirosis in 2023. Additionally, it was reported that the DOH pre-position equipment and medical supplies for flood-borne diseases in all provincials DOH health offices. The DOH recommends that individuals who waded through floodwaters caused by typhoons seek a prescription prophylactic antibiotic.

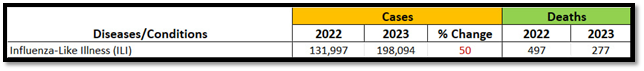

Influenza – The peak flu season in the Philippines coincides with the rainy season. The DOH recommends a yearly vaccine for everyone over six months of age, in line with international recommendations.198,094 cases and 277 deaths were recorded in the country from January 1 to December 2, 2023. This represents a 50 percent increase in cases compared to the same period in 2022.

Potential increase in COVID-19 cases – Some experts have worried that there could be a potential increase in COVID-19 cases corresponding to the rainy season. Similar to the reasons for increased cases of flu cases, if COVID-19 has some seasonality, that seasonality would likely correspond to the rainy season. However, any COVID-19 surge is likely to be less than the previous surges during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Companies can encourage and incentivize boosters, which still have relatively low uptake in the Philippines. According to reports from February 2024, an estimated 78 million Filipinos have completed their primary COVID-19 vaccination series. However, as of that time, only 23.8 million individuals had received booster doses.

Good hygiene can significantly mitigate the risk of contracting rainy season diseases. Hand-washing is essential to stopping the spread of infectious diseases and is an essential practice in the home and on the job, especially for those working in the food processing or restaurant industries. Water-borne diseases can be mitigated by drinking bottled or boiled water and by washing and cooking food properly.

It is also important to wear proper footwear when it rains. It is unsafe to wade into floodwaters as exposed skin can increase the risk of infection. Standing water and refuse should be removed from areas in and around the home since they are potential breeding grounds for mosquitos. To avoid contracting influenza, it is advisable to take your regular flu shot every year.

Taking commonsense precautions can significantly decrease the risk of exposure to dangerous bacteria and viruses – and can mean the difference between good health and illness this rainy season.

Business Disruption in Tag-Ulan

While much of the attention in the media is devoted to natural disasters, executives say that they are more focused on the consequences of flood risk as well as other negative outcomes associated with persistent rain at this time of year. Those consequences may include but are not limited to:

Worksite and Production

- Power interruption/loss of communications/internet connectivity during strong rains or thunderstorms

- Damage or loss to the physical plant and capital equipment due to flooding or seepage at the worksite

- Damage or loss to components or finished goods due to flooding or seepage at the worksite, or inventory stored at the warehouse, or in transit

- Logistics and transportation delays due to flooding or road mishaps that result in failure to meet contractual deadlines

- Loss of revenue due to disruption of business continuity due to above

- Closure of government offices, causing delays in permitting and other processes

- Reputational loss/loss of clientele due to above

Labor Force and Human Resources

- Suspension of work due to government declaration of emergency holiday

- Worker absenteeism due to rainy season-related illness

- Worker tardiness and absenteeism due to flooding and unavailability of transportation

- Lower worker productivity due to so-called “seasonal affective disorder” (SAD)

The best approach to flood risk mitigation would simply be not to build or lease in a flood zone and hire employees who live nearby. But as a practical matter conducting due diligence about a site’s potential flood risk and suitability of the local workforce could be more complex than it might be at first glance appear. It is not enough to take a landlord or estate agent’s word that a site is flood-free. Companies must be proactive and independently verify the site’s resilience to natural disasters.

Generally speaking, PSA believes that geographic data on natural disaster vulnerability is increasingly available ahead of time, through official sources such as Hazard Hunter. But a company must proactively seek out this information ahead of time. During a natural disaster, official communication may be confusing or contradictory. This may stem from systemic issues in Philippine disaster resiliency planning and response, where scientific bodies that contain expertise are not in charge of disaster response and resiliency.

Even tenants whose districts are not historically flood-prone should take nothing for granted. Ensure that qualified experts perform regular inspections of perimeter walls, floors, and roofing for flood vulnerability and leaks. Insurance companies may refuse payment if regular due diligence – typically mandated in the policy – is not performed. This might also include rules on regular maintenance of machinery, vehicles, and other equipment that could be damaged or destroyed by flooding.

Managers attribute the high rate of absenteeism in the rainy season in Metro Manila to the already difficult commute workers face coming from areas to the north and south of Manila – which can take as long as three hours from Bulacan, Laguna, or Cavite even when there is no rain at all.